|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

May

9,

2010,

6th

Sunday

of

Easter

"C" Mississippi Abbey, Iowa, USA HOMILY When you promise

something

to

someone,

and

you

want

to

assure

that

person

that

you

will

really

do

it,

you

may

say

"I

give

you

my

word".

And,

if

you

are

a

person

of

honor,

after

you

have

given

your

word,

you

will

abide

by

that

word. But in other

occasions

you

may

express

exactly

the

same

thing

by

saying:

"I will keep my word". Paradoxical as it may be, to "give one's

word"

and

to

"keep

one's

word"

mean

exactly

the

same

thing. And, by the

way,

this

is

why

silence

is

so

important

in

the

life

of

Contemplative

prayer:

not

because

speech

is

not

important;

but

because

it

is

too

important

to

be

wasted

in

trivial

things. When I give

my

word

I

give

myself,

and

therefore

a

personal

communion

is

established

between

me

and

the

person

to

whom

I

gave

my

word. God has loved

us

so

much,

says

John,

that

he

has

given

us

His

Word.

He

has

given

it

and

has

kept

it.

He

has

given

us

his

own

consubstantial

Word,

his

Son;

and

whoever

receives

Him

and

keeps

Him

is

united

with

God. The Gospel

we

just

read

was

an

answer

of

Jesus

to

a

question

from

Judas And here is

something

interesting

for

us,

monastics.

When

Jesus

says

that

the

Father

and

He

will

come

and

make

their

"dwelling"

with

us,

the

Greek

word

used

is

"monč".

Now

"monč"

is

one

of

the

two

words

used

in

the

Greek

monastic

texts

for

"monastery"

("monč"

and

"monasterion"

are

interchangeable.

And

the

etymology

of

monastery

is

not

the

same

as

that

of

monk.

A

monastery,

etymologically,

does

not

mean

a

place

where

you

find

monks.

The

etymology

of

monč

or

monasterion

means

a

place

where

someone

dwells.

Now,

to

dwell

somewhere

is

not

the

same

as

to

be

somewhere. The meaning of dwelling implies some stability,

some

permanence,

some

satisfaction

or

pleasure.

You

dwell

in

a

place

that

you

have

made

your

own;

your

mind

dwells

on

something

that

is

important

to

you

--

or

on

someone

whom

you

love. This is what

a

monastery

is

all

about:

it

is

a

place

where

a

group

of

persons

dwell

together

on

the

same

Word

of

God;

where

they

keep

together

the

same

Word,

and

are

united

by

the

same

Spirit.

It

is

a

place,

therefore,

where

they

together

expect

the

Visit

of

the

Father,

the

Son

and

the

Spirit,

and

their

dwelling

among

them.

This

is

what

unites

us

into

a

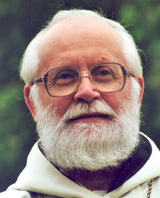

community. Armand VEILLEUX |

|

||

|

|

|||